As the world prepares for the 4th UN Conference on Financing for Development (FfD4) in Seville, I wanted to share a few reflections I brought into recent discussions on Belgium’s positioning.

We know that efforts to mobilise private finance for development have underdelivered. What’s less often discussed is why. After years of ambitious targets, donor coordination, and institutional focus, the “trillions to be mobilised” never quite materialised. While we need to understand why it hasn’t worked, this is only part of the story. The conversation now needs to shift from how much we mobilise, to how we finance development: with what instruments, under what conditions, and for whose benefit.

Why hasn’t private finance mobilisation worked?

Over the past decade, there’s been a lot of talk about unleashing private capital for development, better-known as the “Billions to Trillions” agenda launched at Addis Ababa in 2015. But the results so far have been sobering. MDB efforts to crowd-in private investment have fallen far short of the hype. In 2020, for example, all MDBs combined mobilised only about $61.7 billion from private sources – roughly 1.5% of the estimated $4 trillion annual financing gap for the SDGs. Meanwhile, this drive to “leverage” funds has often warped the purpose of aid. ODA has increasingly been seen as just a tool to derisk private projects, overshadowing its core mission of poverty reduction. We’ve essentially tried to financialise development, but the promised scale hasn’t materialised, especially in crucial areas like climate adaptation, where private money is scarce.

The question is no longer whether mobilisation has fallen short, but why.

That answer lies partly in the modalities of derisking and how financial instruments are being deployed. Drawing from my research on MDBs and financialisation (Bougrea & Vermeiren forthcoming), here are a few structural reasons we must confront.

Project vs. Portfolio Derisking

We must distinguish between project and portfolio derisking — not to choose one over the other, but to understand their limits and logics.

Project derisking remains the dominant strategy. It involves derisking individual projects or local financial institutions. Within the EU, this model is increasingly promoted not to support local entrepreneurship in developing countries, but to align development finance with export credit agencies (ECAs) and promote EU commercial interests. The result? (Limited) financing flows that benefit Global North firms, not local Global South private actors.

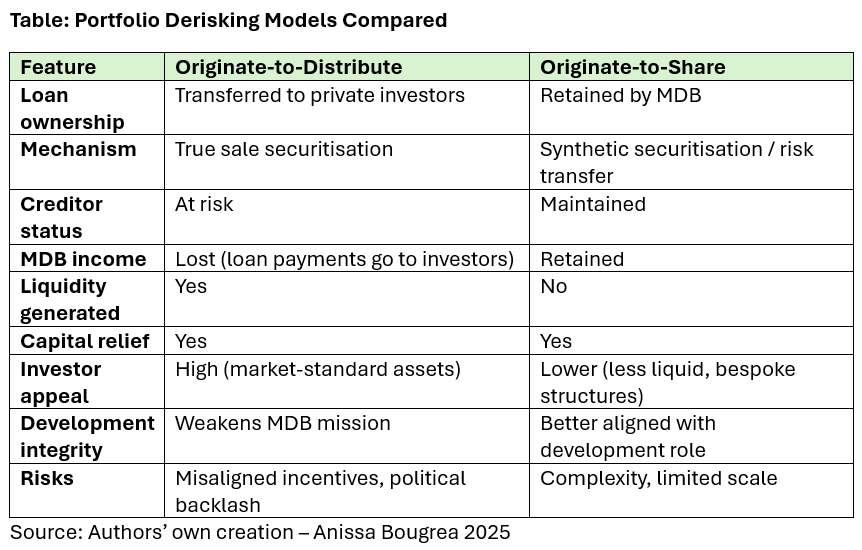

In the push to scale development finance, portfolio derisking is often framed as a promising solution—particularly for mobilising institutional capital. But not all portfolio approaches are the same. In fact, two distinct models exist, and each carries very different implications for how Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) operate and whose interests development finance serves.

The first, known as originate-to-distribute, mirrors the true sale securitisation model popular in commercial banking. Here, MDBs originate loans, then bundle and sell them to private investors, removing them from their own balance sheets. These securitised portfolios are structured into tranches and offered on capital markets as standardised, investment-grade assets. In theory, this frees up MDBs’ balance sheets, offers liquidity, and creates scalable opportunities for institutional investors seeking predictable returns.

But in practice, originate-to-distribute is deeply problematic. It jeopardises MDBs’ preferred creditor status, risks their AAA credit ratings, and cuts off the interest income that funds concessional operations in low-income countries. It can also shift MDB incentives away from high-impact, high-risk public lending toward bankable projects in middle-income countries—aligning more with investor expectations than with development needs. Politically, it risks turning MDBs into originators for capital markets, not lenders for development.

The second model, originate-to-share, offers a more cautious and development-aligned approach. Here, MDBs keep the loans on their books, but transfer part of the credit risk to investors through mechanisms like guarantees, credit default swaps, or structured risk tranching. Unlike full securitisation, this approach retains MDB ownership and governance over loans, allowing them to preserve their role as long-term, reliable development partners. Because MDBs remain the lender of record, this model preserves creditor status, avoids selling off development loans to unknown third parties, and maintains more transparency and accountability.

Still, originate-to-share has limitations. It provides capital relief, but not liquidity. Structuring these transactions is also more complex and often requires bespoke arrangements—limiting their scalability. And because these portfolios must still be structured into risk-tiered tranches, this model, too, can incentivise a shift toward standardisable, marketable assets, albeit more subtly.

In short: both models present trade-offs. Originate-to-distribute is more attractive to capital markets but risks hollowing out MDBs’ development function. Originate-to-share is safer for preserving MDBs’ public mandate, but faces structural and political limits to scale.

Both approaches assume private capital is waiting on the sidelines, but the reality is more complex. Without standardised, liquid, and large-scale products, institutional investors will not engage. However, not all development goals can -or should- be made “bankable”, nor standardised. We should be cautious about a securitisation-driven agenda. Chasing private investors at any cost could even entrench financial instability and leave the poorest countries behind. The 2008 crisis taught us that bundling and trading loans isn’t without risk – do we want to import those risks into development finance?

Better, Bolder, and Bigger MDBs?

There’s a growing recognition that we’d be better off strengthening MDBs’ traditional public finance model instead. In practice, that means empowering MDBs to lend more, on better terms, directly to countries that need it, rather than primarily trying to entice private financiers. How? For one, implement the G20’s recommendations on MDB capital adequacy – adjust those overly conservative rating methodologies so MDBs can use their balance sheets more effectively.

Shareholders should also consider capital increases (yes, more public money upfront) and creative tools like rechanneling SDRs or deploying hybrid capital, so MDBs can expand lending without compromising stability. Crucially, we need MDBs to maintain their role as reliable, long-term partners to developing countries – for example, by ramping up counter-cyclical lending that kicks in when market flows retreat. These steps aren’t as glitzy as securitization, but they can significantly boost development finance while keeping the focus on development outcomes.

Instead of choosing sides in the project vs. portfolio debate, we should:

🔹 Strengthen MDBs’ traditional public lending role through reforming capital adequacy frameworks (CAF), reallocating Special Drawing Rights and considering capital increases.

🔹 Apply instruments contextually: neither model is a one-size-fits-all solution

🔹 Adopting a holistic approach: tackling debt, domestic resource mobilisation, and tax justice

🔹 Reconnect with development purpose: prioritise local ownership, fiscal space, and long-term outcomes over short-term “mobilisation” numbers

The growing focus on mobilising private finance has shifted attention from development goals to financial engineering, and has quietly transformed not only the volume of resources we seek, but the modalities and rationales behind how we deliver development finance. Whatever path is taken, a few core principles must remain front and center:

Not all capital is equal: context matters

The same financial instruments (NDICI-Global Europe) are used across development, sustainability, and climate agendas. The difference lies not in the tool, but in how and why it is used. It’s vital to use the right instrument for the right context. Grants, loans, guarantees, equity, public-private partnerships – each has its place. We shouldn’t force every situation into a blended finance mold. The Global South is not a monolith: a fragile low-income country and a middle-income emerging market have very different needs and risk profiles. Development finance has to be tailored – one size does not fit all. We must ask: what is the purpose of this instrument? And is it appropriate to the context in which it is being deployed?

We need to resist a logic where instrument choice is driven by where the capital wants to go, rather than by what the context actually needs. When instrument design is meant to serve export credit goals or EU commercial interests, rather than local development priorities, we lose sight of purpose. We need to re-centre development logic in the way we deploy instruments. That means respecting additionality, recognising when public finance is irreplaceable, and choosing tools based not on scalability or bankability, but on what best supports long-term, equitable development.

Similarly, calls to create new, ever more specific instruments for climate or green objectives may seem strategic, but they risk fragmenting ODA and making aid more vulnerable to being redirected toward commercial or geopolitical goals. Coherence is key: our development, climate, and finance strategies should work in concert, not at cross purposes. We shouldn’t set up siloed funds for climate or infrastructure that end up serving narrow interests; all tools need to align with the overarching goal of sustainable development.

The test for Seville is not whether or how we can mobilise more capital, but whether we are willing to commit to a more equitable world. Hunger has increased since 2015, the very year the SDGs were launched, despite unprecedented global wealth ($115 trillion world GDP!). We must confront the uncomfortable truth: these outcomes are not the result of scarcity, but of political and moral choices.

Leave a comment